I haven’t been making art since the beginning of 2010. If you’re a close friend or family member this shouldn’t be big news, but then again it’s not something I talk about all too much. Prior to my decision I was drifting along painting at work and home going through the motions. Not having a proper studio space didn’t help ($$$), but I was no longer excited about my work, the ins and outs of the art world were becoming a turn off and the long shadow of grad school was weighing me down.

Although I had the time of my life at CalArts it was also an intellectual struggle that’s persisted to this day. Going in I was a very intuitive artist. I would typically let my imagination spew out on paper with little regard for theory or conceptual justification, which are major players at CalArts. Art was a playful exercise and by the end of grad school it turned into mental gridlock. Questions and doubt plagued every artistic move. What does this mean if I do that? How will it be interpreted? It has to mean something.

This ongoing debate was making me miserable so I decided to throw myself into some other creative outlets. NIAD has also been a nice antidote. The artists who work there are mostly free of the aforementioned dilemma. They put pen or paint to paper and simply create. I tried to work like this in undergrad, at least as much as I could. A lot of artists wish they could completely block the left side of their brain. It’s nearly impossible for most, while others through misfortune don’t have a choice.

Last month I had a wonderful encounter with the artist James Pitt. He works in the Mission District of San Francisco and I paid him a studio visit on behalf of NIAD. A friend thought James might appreciate NIAD art and encouraged him to contact me via e-mail.

Pitt graduated with his MFA from Mills College in 2003, the same year I finished at Cal Arts. He was making art and teaching at the California College of the Arts until 2007, when a street sweeper hit his car head on in Sonoma. The terrible accident left him with a variety of debilitating injuries and long-term disabilities. He has chronic memory loss, trouble focusing at times, has difficulty reading and some physical limitations, all of which you would never comprehend if you met him in person.

His studio is in a converted attic with a single skylight that floods the room with a soft glow. He shares the space with a housemate. Pitt primarily makes sculpture, which is supplemented by drawings. The 3D work is essentially abstract, built from cardboard, wood, clay and is coated with various shades of white, grey and beige with a bit of color thrown in from time to time. They’re personal in size and can occupy a small shelf or pedestal without trouble.

Prior to the accident Pitt was a self-described conceptual artist. He would thoroughly research his subject matter and create highly complex work. He now spends his time trying to capture memories and shapes that have occupied his psyche, but struggle to flow from his fingertips. His practice is entirely different from subject matter to creative process.

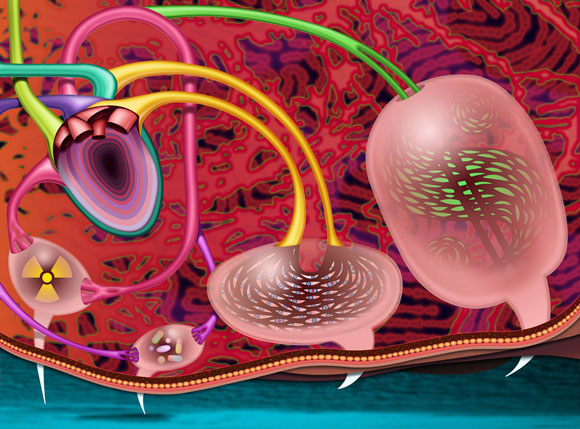

His drawings are a good place to start when contemplating his work. It’s where he tries to organize his thoughts and make sense of the information he encounters every day or that clouds his memory. Large sheets of paper are filled with row after row of shapes. Most are rectangular figures that seem to evolve as they cross the page. They grow arms, intertwine and sometimes turn into recognizable objects like shoes or books. Occasionally, words dot the page in the form of titles or phrases, but this is a recent development.

The three dimensional work emerges from these sketches and the forms take shape from plywood or cardboard with help from a knife or jigsaw. It’s the only power tool he feels comfortable using, which may sound like a limitation, but the irregular lines and shapes it produces evokes the hand drawn sketch and makes them appear whimsical. The flat pieces are then pieced together, painted and primarily form irregular circles filled with interlocking lines, protruding orbs and sometimes hold wire or mesh.

Despite his limitations Pitt has found success. His new work has been widely exhibited through gallery representation in San Francisco and Berlin, where he was preparing to ship his latest sculptures. The pieces are also fetching good prices, a small collector base has formed and he recently received a nice review from San Francisco Chronicle art critic Kenneth Baker.

Pitt and I spent an hour talking about the work. It had been awhile since I sunk my teeth into art speak and I thoroughly enjoyed the moment. I asked a lot of questions. I was curious about color and material choices, but his creative process primarily intrigued me and how the artwork was now free of conceptual underpinnings. The more I learned the more I found myself in the awkward position of admiring the outcome of his hardship. I would love to dump the conceptual baggage that nags at my own creative psyche. I just wish it didn’t take a car accident to achieve that goal.

Let me be clear, I don’t regret my creative path and I haven’t given away my paint brushes. I received a fantastic education and made some great friends. As time goes on and I’m slowly removed from those days in graduate school I’ll find the inspiration to create again and my visit with James Pitt was a good start.